If a child were accommodated at a youth detention centre, then generally they would have:

- their own cell (with privacy from other children offered when they shower and use the toilet)

- a common area where they can interact with other children during the day

- an adjoining outdoor exercise yard that is also accessible during the day.

It would also be expected that they would have access to other outdoor areas, including an oval, to exercise and play sport.

Layout

Cairns watch-house

The Cairns watch-house was built in 1992. It has:

- 18 accommodation cells (most with two built-in bed bases and some with three)

- three detainee common rooms

- two isolation cells

- two padded cells

- four holding cells

- one exercise yard with access to the open air

- two interview rooms, one of which is non-contact.

We were told that up to 40 individuals can be accommodated (or 42 if the two isolation cells are used) when the watch-house is being used to its built/designed capacity.

The accommodation cells are divided into four distinct areas (units). Each unit has a corridor (spine) with a number of accommodation cells coming off it. The spines are separated by doors from other units and/or other corridors. The four accommodation units are made up of:

- the Men’s unit, with 11 accommodation cells and two common rooms with televisions

- the Women’s and girls’ unit, with four accommodation cells and one common room with a television

- the Boys’ unit, with three accommodation cells and no common room

- isolation cells, which are two standard single accommodation cells with no common room.

We observed that the areas the detainees use are of a design that offers ligature point reduction (which means that ‘hanging points’ are minimised).

Most areas of the watch-house, including cells, common rooms and the exercise yard, are covered by closed-circuit television cameras (CCTV), with monitors located in the officers’ area. The CCTV system features a black square on each monitor that covers the toilets, to block out the footage of a detainee using one of them. There is no CCTV coverage of any of the showers.

With the exception of the outdoor exercise yard, there is no natural light in the watch-house. There are no windows to the outside, either in the accommodation cells or common rooms. Research has demonstrated that access to natural light can impact on a detainee’s overall wellbeing.

Because of this alone, the Cairns watch-house should not be used to accommodate children for longer periods of time.

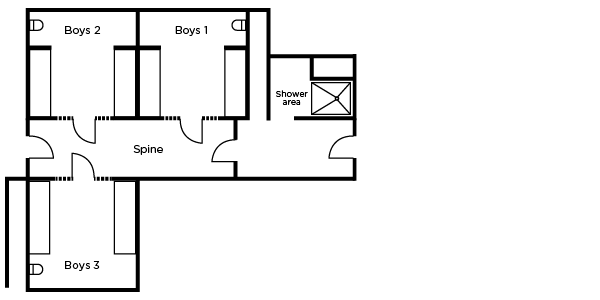

Boys’ unit

The Boys’ unit is separated from the other accommodation units by doors at the end of the spine, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Floor plan of the Boys’ unit at Cairns watch-house

Source: Office of the Queensland Ombudsman using information provided by the Queensland Police Service.

This has the advantage of allowing for physical separation from adult detainees and girls (although noise tends to travel around the whole watch-house). However, at times there are not enough cells for the number of boys in the watch-house, and some are held in cells in the Men’s unit. We discuss this in more detail in the following section on accommodation cells.

Photo 1 – The spine of the Boys’ unit. (Lunch had just finished and the unit had not yet been cleaned, so there is some rubbish visible in the photo.)

A significant disadvantage of the infrastructure as it relates to boys is that (as already noted) there is no common room or television attached to the unit. This means there is no dedicated area where boys can interact and watch television during the day. During the inspection, we saw boys with their mattresses on the floor at the doors of their cells, so they could converse with boys in other cells.

While they have access to the outdoor exercise yard, it is limited – often to an hour a day. Time in the exercise yard needs to be allocated to other groups (adult male detainees, adult female detainees, girls, and detainees who are in isolation). We were also told that watch-house staff try to give the boys time in one of the men’s common areas when the men are in the exercise yard. However, this is dependent on operational requirements, is only for about an hour, and is never guaranteed.

The combination of a lack of dedicated common room and a lack of access to an outdoor exercise yard can increase feelings of isolation and boredom. Over extended periods, this may negatively impact on the boys’ wellbeing. It is also inconsistent with relevant standards.

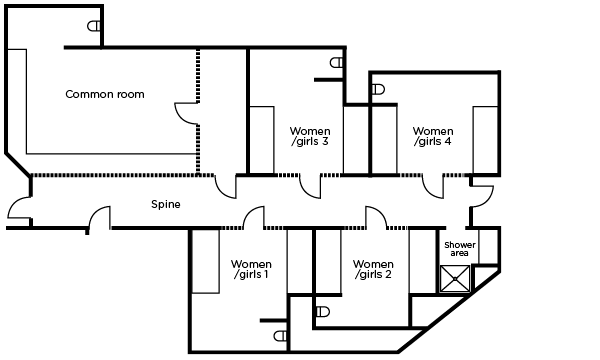

Women’s and girls’ unit

Unlike the Boys’ unit, the Women’s and girls’ unit has a common area/television room.

Photo 2 – Common room similar to the one located in the Women’s and girls’ unit.

We observed two girls using this room for significant periods of the day, watching television together (which is one of the limited number of activities available).

A disadvantage of this accommodation is that adult female detainees and girls may be in the same unit. Even though they physically cannot access each other (they are always separated by at least one or two doors), they are able to communicate, as the cell doors open into the common spine, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Floor plan of the Women’s and girls’ unit at Cairns watch-house

Source: Office of the Queensland Ombudsman using information provided by the Queensland Police Service.

Section 16.12.1 of the Queensland Police Service’s Operational Procedures Manual (OPM) states that ‘children are not to be placed in the same cell as an adult prisoner, unless there are compelling reasons in the child’s interests’, for example:

… the custody of an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander youth with an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander adult prisoner may be safer than isolation where the child is agreeable, and the adult is the same gender.

While placing girls and adult women in the same unit does not breach the OPM requirement, we are concerned that it provides an opportunity for an adult detainee to communicate with a child. This could mean verbal abuse, threats or other inappropriate communication.

Murgon watch-house

The Murgon watch-house was built in 2010. It has:

- five individual accommodation cells (four with a two-bed capacity and one single cell)

- two common rooms

- one padded cell and one holding cell

- one non-contact interview room

- no usable outdoor exercise yard.

As four accommodation cells have double capacity, nine individuals can be accommodated under the watch-house’s designed/built capacity.

The accommodation is divided into two distinct areas:

- Unit 1 has three accommodation cells (two double and one single), which open onto a common room/television area, with a shower accessible from the common room.

- Unit 2 has two accommodation cells (both doubles), which open onto a common room/television area, with a shower accessible from the common room (see Figure 5).

As we will discuss below, these two units are used in a flexible manner, and various configurations are used to accommodate men, women, boys and girls (depending on the mix on any given day).

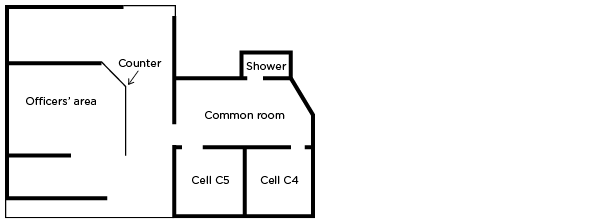

Figure 5 – Plan of Unit 2 at Murgon watch-house

Note: The plan is not to scale.

Source: Office of the Queensland Ombudsman using information provided by the Queensland Police Service.

Both units are adjacent to a large, open-plan area that contains a reception counter and officers’ area. The wall between the accommodation units and the cells that adjoin the officers’ area is made of a glass-type material with internal blinds. When the blinds are open, officers can see directly into the common areas and some cells. This provides much greater visual connection between officers and detainees than the Cairns watch-house has.

We observed that the areas of the watch-house used by detainees are of a modern, ligature point-reduced design (again, reducing hanging points).

All key areas of the watch-house, including cells, are covered by CCTV, with monitors located in the officers’ area. (There are no privacy squares on the monitors in the areas of the toilets.)

Unlike Cairns, Murgon has windows to the outside from the common areas and some cells that allow some natural light to enter both units.

Accommodation for boys and girls

Unlike Cairns, Murgon’s infrastructure does not allow for discrete areas to accommodate boys and girls, so the accommodation units are used flexibly, depending on demand.

During our visit, two boys were being accommodated in Unit 2 (Cell C4) and one girl was being accommodated in the same unit (Cell C5). While this allowed for separation of children from adults, it did not allow for complete separation of the boys from the girl.

At times during our inspection, the two boys were in the common room when the girl was in her cell. Section 16.12.1 of the OPM states that ‘male and female prisoners are not to be held in the same cell or permitted direct access to each other in other areas within a watch‑house’.

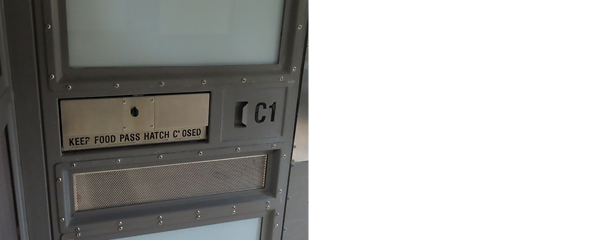

There is no direct access, but because the cells open directly onto the common area, the boys could communicate with the girl or look into her cell through a mesh panel inserted into the door (see photos 3 and 4).

Photo 3 (composite image) – Murgon watch-house common room with two cells (C4 and C5) opening onto it. This photo also shows the shower access and the mesh in the cell door (lower right).

Photo 4 – Close-up of mesh panel in cell door in Murgon watch-house.

Photos 5 and 6 – Inside Cell C5 in Murgon watch-house.

Children cannot be completely separated from adults when men, women and children are accommodated in the watch-house at the same time. We were told that adults and children never share a cell, and men would never be placed in the same accommodation unit as children. However, as mentioned previously, women sometimes are.

One advantage of Murgon over Cairns is that each unit has its own common room with a television. (See Photo 3.) This means that, depending on the mix of detainees on any given day, children are likely to spend time in the common room, mixing with other children and/or watching television.

Watch-house staff advised us that they prioritise Cell 4 for children, as it allows them to watch television from the inspection slot of the cell. We observed that children had placed their mattresses on the floor of Cell 4 near the door to do this.

Accommodation cells

Cairns watch-house

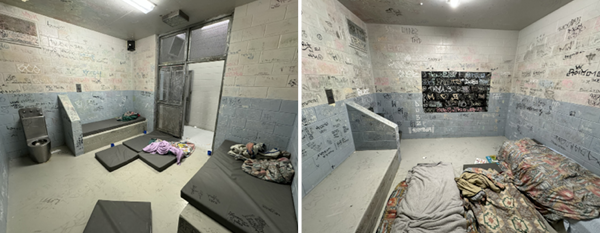

The cells used to accommodate children and adults in the Cairns watch-house are generally similar in size and design. They contain two or three raised concrete platforms for mattresses to be placed on. The size of the cells appears adequate for the accommodation of two people.

In the Boys’ unit, the three cells can accommodate two boys each. At times, however, more than five boys are held in the watch-house. During our inspection, two of the boys’ cells were accommodating three boys each, meaning at least two (one in each room) had to sleep on mattresses on the floor.

Photos 7 and 8 – Accommodation cells in the Boys’ unit at the Cairns watch-house.

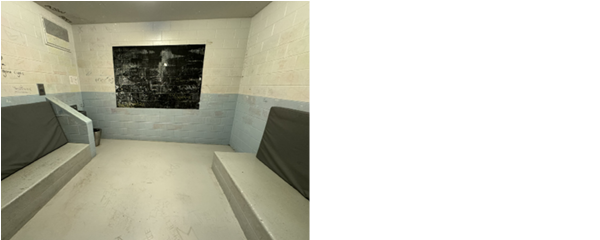

Photo 9 – An accommodation cell in the Women’s and girls’ unit at the Cairns watch-house.

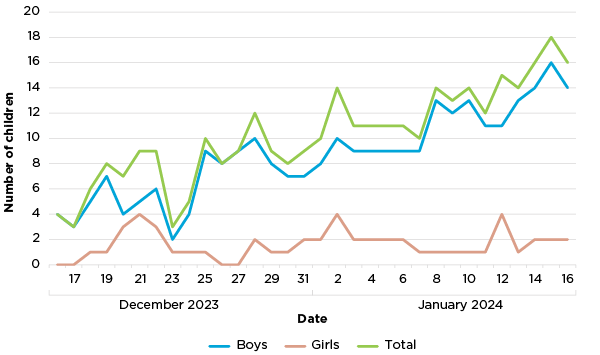

We reviewed Queensland Police Service records for the period from 16 December 2023 to 16 January 2024, which included the three days during which we carried out our onsite inspection. As shown in Graph 3, in that time, the number of boys in the watch-house ranged from two to 16 and the number of girls ranged from zero to four.

Graph 3: Number of boys and girls in the Cairns watch-house 16 December 2023 to 16 January 2024

Note: This shows the number of children who were in the Cairns watch-house as at 5.00 am or 6.00 am on each day, apart from 18 and 25 December 2023, when it was at 2.00 pm.

Source: Office of the Queensland Ombudsman using information provided by the Queensland Police Service.

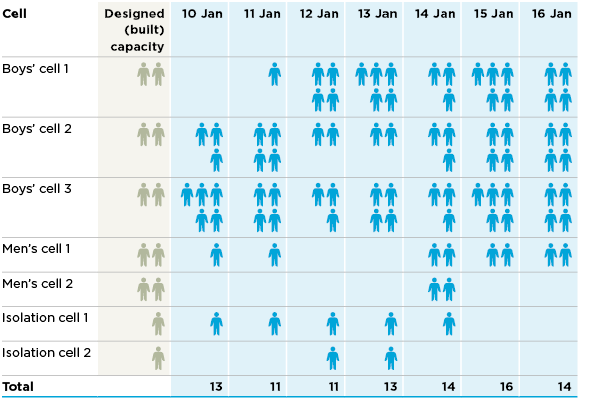

As shown in Graph 3, up to 16 boys were held overnight at the watch-house in the period from 16 December 2023 to 16 January 2024. With only three Boys’ unit cells, each designed to accommodate two people, it means these boys were held in overcrowded cells in the Boys’ unit, in isolation cells, or in cells in the Mens’ unit, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Number and location of boys held in Cairns watch-house – 10 to 16 January 2024

Note: This shows the number of children in the Cairns watch-house as at 5.00 am or 6.00 am each day.

Source: Office of the Queensland Ombudsman using information provided by the Queensland Police Service.

We acknowledge that it may be preferable for children to share a cell, particularly given the lack of areas to interact and activities available to them. Sharing a cell allows them to interact with each other. But care needs to be taken to ensure there are no specific risks that may be posed to any of the children when sharing.

Having many children sharing a cell gives them no privacy and increases the potential for conflict.

The lights in the accommodation cells and spine areas are dimmed overnight, but never turned off. We were advised that this is to allow staff to conduct overnight cell checks on detainees. We understand that some children complain about the impact this has on their sleep.

Accommodation cells – Murgon watch-house

The accommodation cells throughout the Murgon watch-house are largely the same as each other. With the exception of one cell in Unit 1, they contain two raised concrete platforms for mattresses.

We observed up to two children being accommodated per cell.

As with Cairns, while lighting in the accommodation cells and common areas can be dimmed, it is left on overnight.

Photo 10 – Cell C4 at Murgon watch-house, with mattresses on the floor so children can watch television on the opposite wall of the common room through a slot or mesh in the cell door.

Privacy

Toilets

Each cell has one toilet located in one of the far corners. A basin with access to running water is located above the toilet cistern.

Photos 11 and 12 – Cell toilet in Cairns cell. Photo 12 shows the view of the toilet from one of the beds.

Photos 13 and 14 – Cell toilet in Murgon cell. Photo 13 shows the proximity of the bed adjacent to the toilet.

The toilets have a partial wall that provides some privacy in terms of the view from the spine into the cell. It provides little privacy from others in the cell, especially when three or more children are sharing it. There is a bed adjacent to the toilet (see Photos 12 and 14).

In the Cairns watch-house, we saw children using their mattresses to surround themselves in an attempt to get privacy when using the toilet. We were advised that this is a common practice, and that children do the same at Murgon.

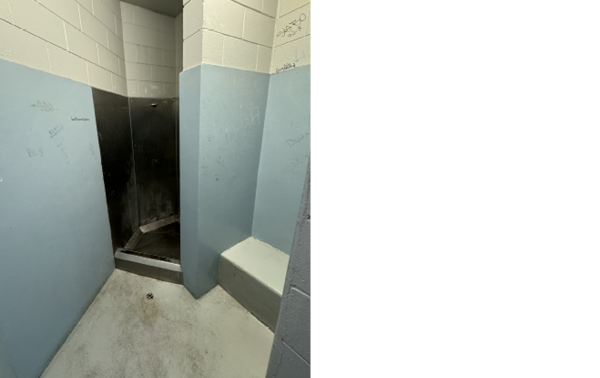

Showers

In the Cairns watch-house, each unit has its own shower area. We were told children are offered daily showers and given a clean towel and soap and shampoo for every shower.

The shower area has no door from the spine (see Figure 4). This means there is a risk that staff and/or detainees can see a child in the shower from the spine when walking past. We are concerned that this lack of privacy may not meet the international standards identified earlier in this chapter.

Photo 15 – Shower in the Women’s and girls’ unit at the Cairns watch-house, as seen from the doorway.

In the Murgon watch-house, as mentioned previously, each common room has a shower attached to it. We were told by watch-house staff that children are offered daily showers, and we confirmed this through a review of a sample of children’s detention files. We also observed children being provided with a clean towel, soap and shampoo on each occasion.

The wall that adjoins the common room is made from a glass-type material; however, most of the door and the wall is covered in an opaque material, which means only the feet of a child would be visible while in the shower areas (see Photo 3 for shower location). This design offers more privacy than the showers at the Cairns watch-house.