Why is overcrowding a problem?

Overcrowding detrimentally impacts prison officers and prisoners, and places strain on prison infrastructure. QCS recognises that shared cells and additional prisoners accommodated in residential units is not ideal and that it presents additional challenges for CCOs and prisoners (see Appendix B).

Impacts on prison officers

A key issue raised in the reference was the impact of overcrowding on the health and safety of CCOs.

In its 2019 Taskforce Flaxton report, the Crime and Corruption Commission observed overcrowding can increase prisoners’ anger and frustration and increase the risk of serious assaults against staff. Its analysis of data in the five years prior to the report showed prisoner-on-staff assaults had increased as the utilisation rate of prisons increased.

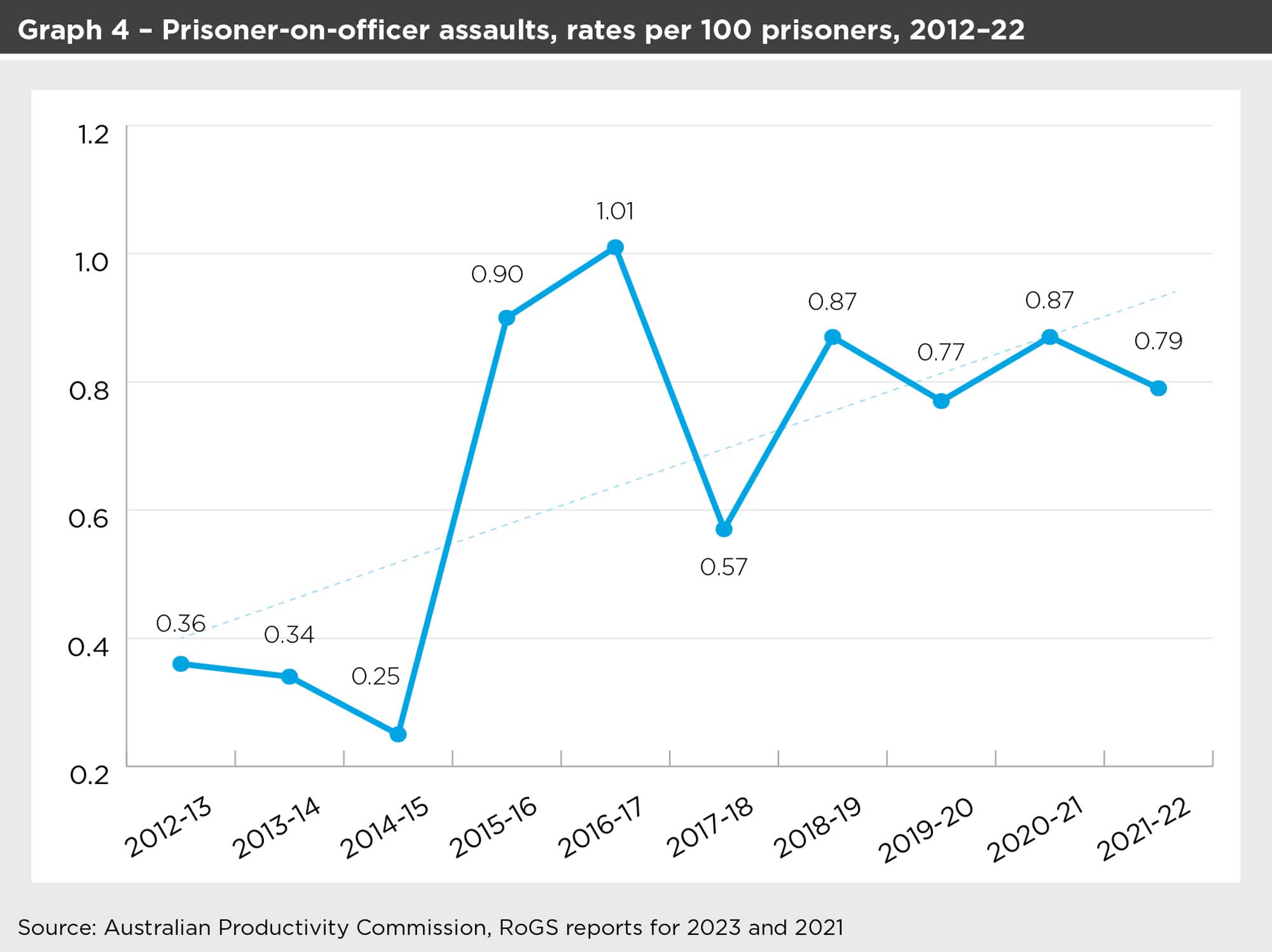

The following graph, sourced from the Australian Productivity Commission RoGS, shows trends in prisoner-on-officer assaults in the financial years 2012–13 to 2021–22.

The most extreme increase in assault rates on officers was from the years 2014–15 through to 2016–17, which coincides with the initial periods of accelerated growth in prisoner numbers, and the onset of overcrowding (see Graphs 1 and 2 above). Also, according to the Queensland Parole System Review, the initial responses to overcrowding were often crude, with extensive reliance on double up placements in cells designed for individual prisoners, using temporary bunk beds, trundle beds and mattresses. These conditions could result in prisoners sleeping with their heads next to a door or an exposed toilet.

From 2017–18, the rate of assaults reduced somewhat, although it continued to remain above 2014–15 levels. This reduction may be associated with additional staffing, additional cells being commissioned and the rollout of the bunk bed program.

Rates of assault from 2020 onwards are likely affected by the management of Covid-19 in prisons, including measures that reduced prisoner movements and time out of cells.

Considered overall, the above data shows the observation of Taskforce Flaxton in 2019 that overcrowding of prisons has coincided with increased rates of assaults on prison officers has continued to the present.

Overcrowding has other impacts on officers, such as the increased administrative burden of making accommodation decisions for prisoners, particularly decisions about which prisoners should share cells with which other prisoners (this issue is considered further in Chapters 4 and 5). In its Taskforce Flaxton report, the Crime and Corruption Commission also observed overcrowding created an increased risk of corrupt conduct.

When QCS was asked for comment on issues impacting staff, it advised it is increasing frontline staff numbers and promoting an integrated and coordinated approach to officer health, safety and wellbeing (see Appendix B).

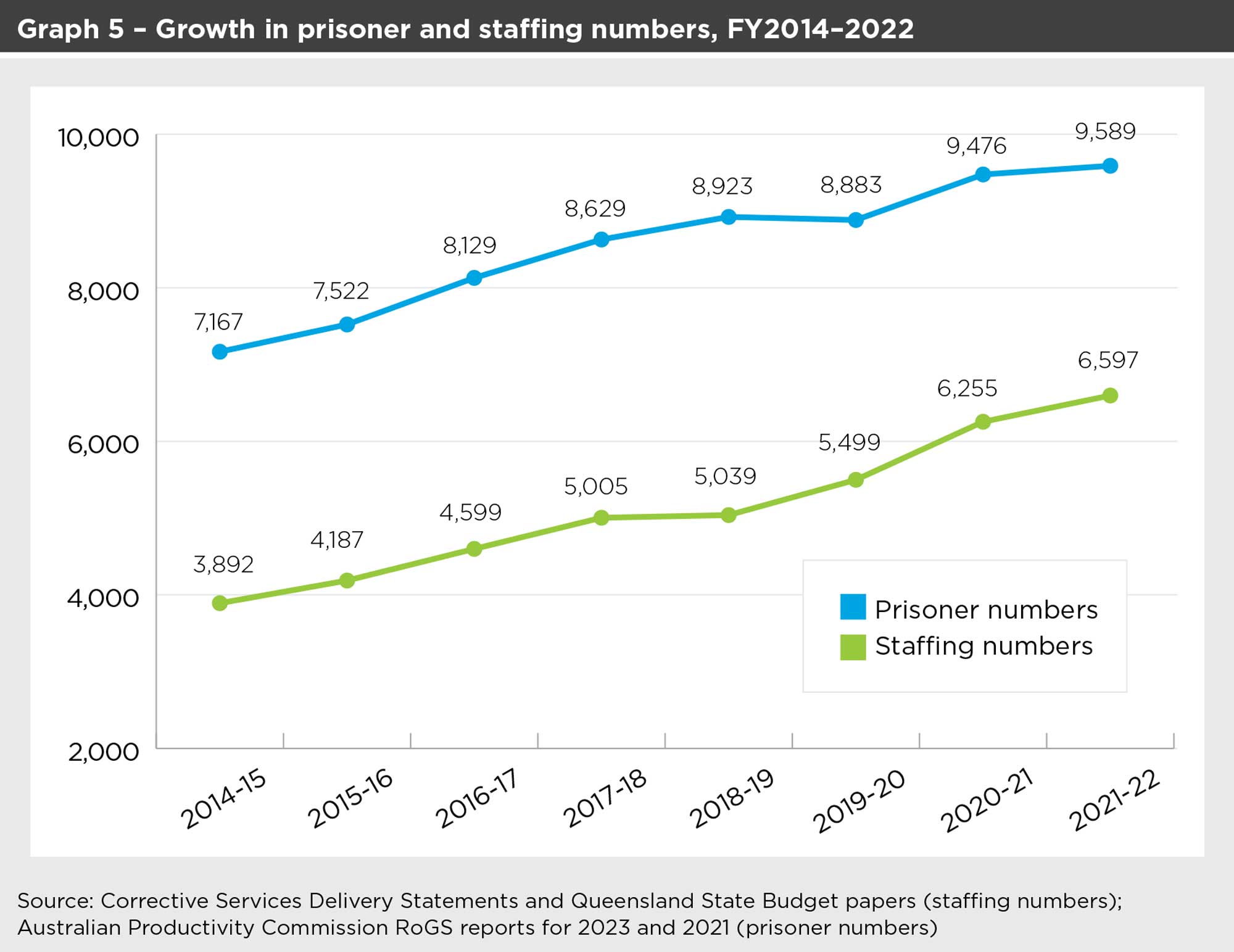

In relation to increasing staffing, QCS advice in October 2022 was that it had budget

full-time equivalent (FTE) staff of 6,245 for 2020–21, representing an increase of 480 staff from the 2019–20 adjusted budget of 5,765 FTEs. As shown in Graph 5, this growth in staff reflects similar growth in the years since overcrowding began.

QCS also cited a number of health and safety initiatives to respond to safety impacts on officers, including:

- Partnering with Workplace Health and Safety Queensland to improve systems and practices for health, safety, injury management and wellbeing

- Site visits and reviews of the QCS safety management system conducted after being significantly impacted by restrictions associated with the pandemic

- Participating in the Injury Prevention and Management Program facilitated by the Office of Industrial Relations

- Allocation of additional body worn cameras

- Undertaking the Officer Safety (Use of Force) Review.

More information about these initiatives is available in Appendix B.

Impacts on prisoners

Overcrowding has a significant impact on prisoners. The Crime and Corruption Commission in its Taskforce Flaxton report outlined those impacts as follows:

Overcrowding affects virtually every aspect of the custodial environment.

It increases prisoner demand for infrastructure, resources and services, and changes the way custodial services are delivered. For example, overcrowding:

- Makes prisoner classification and separation difficult. A lack of adequate space sees prisoners doubling up in cells originally designed for one person or accommodated on mattresses in common areas in residential units. Failing to appropriately separate vulnerable prisoners or prisoners who committed minor offences from more serious and violent offenders undermines prisoner safety and can lead to further criminalisation.

- Negatively affects the provision of efficient and effective health care services to prisoners. A recent review of offender health services in Queensland found that there is limited capacity for these services to cope with overcrowding due to the finite physical footprint of prison health centres.

- Places strain on critical prison infrastructure, systems and utilities (e.g. water, sewage, sanitation, heating and cooling), which can negatively impact prisoner health.

- Further deprives prisoners of their already limited access to resources, including access to kitchen equipment and telephone calls.

- Diminishes prisoners’ capability for a meaningful “constructive day” and could lead to breaches of international obligations. Where prisoners are not meaningfully occupied through time-out-of-cell or participation in employment programs, education or rehabilitation programs, boredom can set in.

- Is related to decreases in prisoner employment and time-out-of-cell.

Less time-out-of-cell was also related to more prisoner-on-prisoner assaults, self-harm incidents, and incidents requiring the use of force.

Similar impacts have been identified in other independent reports. For example, the New South Wales Inspector of Custodial Services in its 2015 report Full House: The growth of the inmate population in NSW noted:

Confining two or three inmates to cells designed for one or two for prolonged periods, where they shower, eat and defecate, inevitably raises tensions in an already volatile population. The experience in other jurisdictions has been that this potentially increases the risk of assault, self-harm and suicide and more general prison disorder. Rehabilitation outcomes are also compromised when inmate numbers are increased without a commensurate increase in appropriate resources. Overcrowding limits opportunities for parole because access to required programs is constrained. Reduced access to work and limited contact with families contribute to the creation of an unproductive environment.

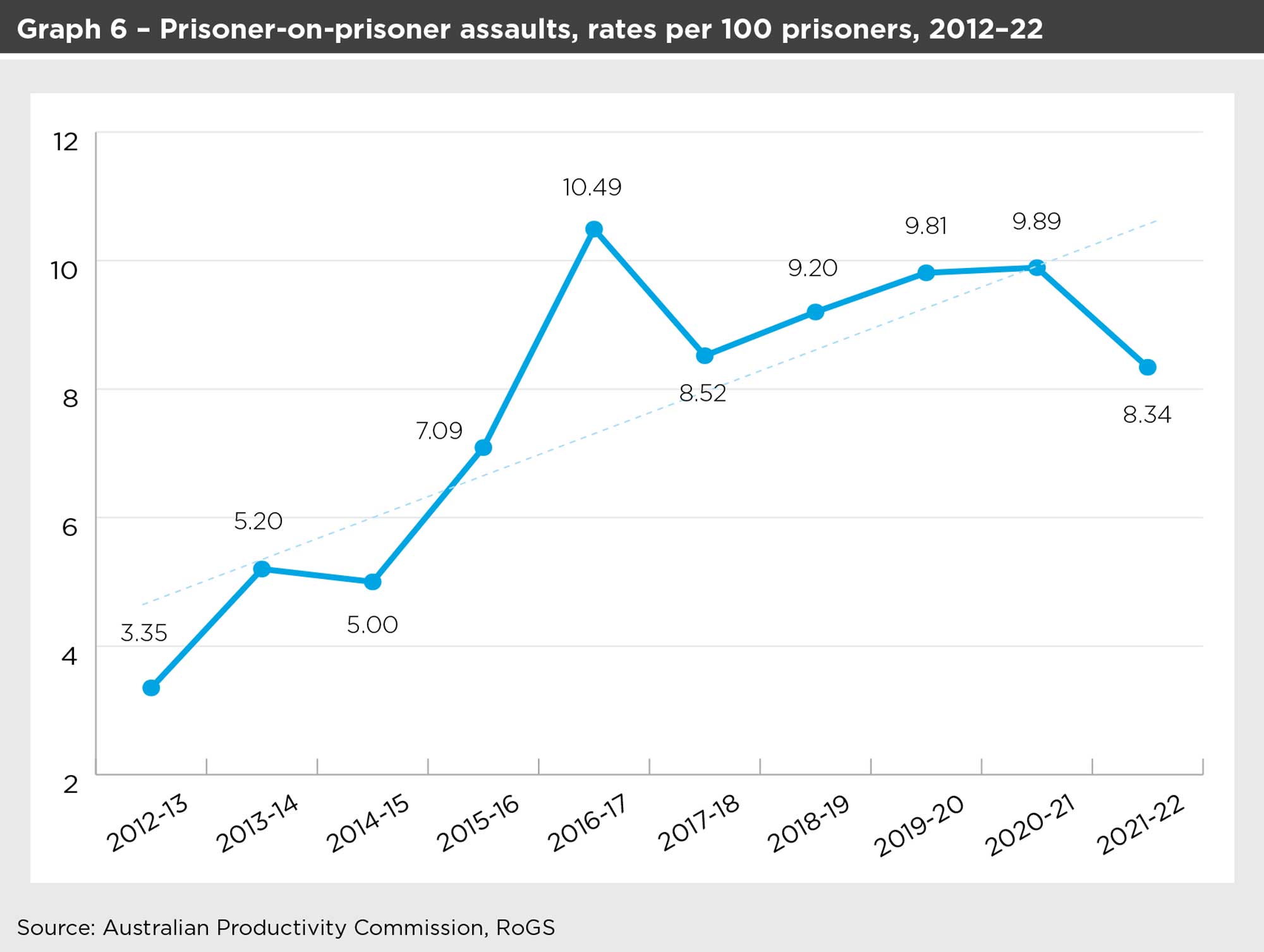

Just as there is a correlation between overcrowding and rates of prisoner-on-officer assaults, the rates of prisoner-on-prisoner assaults has also increased.

The following graph, sourced from the Australian Productivity Commission RoGS, shows trends in prisoner-on-prisoner assaults in the financial years 2012–13 to 2021–22. The interpretative observations about Graph 4 above apply equally to Graph 6.

Another impact of overcrowding on prisoners is reduced out of cell time. According to the Australian Productivity Commission RoGS reports for 2023 and 2021, time out of cells (average hours per day) in Queensland declined from 11.2 hours in 2010–11 (prior to the onset of overcrowding) to only 8.4 hours in 2021–22. In 2019–20, the last reporting yearbefore Covid-19 responses may have significantly impacted time out of cells, the number of hours was 9.0 hours. This represents a decline of 19% in time out of cells between 2010–11, when prisons were not overcrowded, and 2019–20.

One reason for the decline is that when centres are overcrowded, or when there is insufficient available staffing, out of cell time can be reduced by the use of ‘modified unit routines’ (MURs), where only half the prisoners in an accommodation unit are allowed out of cells at a time (e.g. one group in the morning, the other in the afternoon), leading to significantly reduced time out of cells for prisoners.

During the visit to MCC, advice was received that prisoners in secure custody were out of their cells for only four to nine hours per day, depending on the management routine for the particular unit. Further information is contained in the next chapter.

In addition to increased assaults and reduced out of cell time, overcrowding also impacts on prisoners through the requirement for them to share cells designed for one prisoner, sometimes referred to as ‘doubling up’.

There are several potential negative impacts of ‘doubling-up’, including lack of privacy and safety, and increased potential for violence. The studies currently available in a European context seem to suggest that the impact of cell sharing in overcrowded conditions is especially negative, linking it to tense prison social climates, higher levels of assault, bullying and increased rates of suicide and self-harm. While research conducted in Ireland on the issue of cell sharing reveals a relationship between cell sharing and wellbeing for some prisoners, it indicates that cell mate relationships may be more important than cell type in influencing wellbeing (Muirhead, Butler & Davidson, ‘Behind closed doors: An exploration of cell-sharing and its relationship with wellbeing’, European Journal of Criminology).

While the bunk bed program has reduced some of the worst impacts of shared cell agreements (such as prisoners being required to sleep on mattresses on the floor with their head close to the cell’s toilet or door), significant problems remain.

During the investigation’s visit to MCC, many secure custody cells were observed in which two prisoners were accommodated on double bunks in small cells originally designed for a single prisoner, with access to a single desk, toilet and shower. Other visits to correctional centres by this Office indicate that double bunks are of varying quality, with not all having ladders to the top bunk, for example.

Based on observations during the above visit, the following extract from the 2021 Capacity Utilisation Review of the Office of the Custodial Inspector of Tasmania about similar cells in Tasmania’s prisons is applicable:

In terms of toilet and ablution facilities, the lack of fully partitioned rooms in cells for ablutions means that toilets must be used in front of other prisoners. While showers are partially screened, the space is minimal … Dressing normally occurs in the limited habitable space of the cell. Similarly, it is difficult to fully accommodate the sleeping and relaxation needs of prisoners in a shared cell environment. All of these factors impact on the mental health, dignity and privacy of prisoners through the inability to keep the private and personal aspects of their lives separate from another prisoner.

During the MCC visit, prisoners and staff discussed the mental health impacts on prisoners of sharing cells. Further information about this is contained in the next chapter.

Impact on service delivery and infrastructure

A lot of the concern about overcrowding is justifiably on the safety of officers and the individual experiences of prisoners within cells. However, as noted above in the Taskforce Flaxton and New South Wales Inspector of Custodial Services reports, overcrowding also causes broader cumulative impacts across prisons, as services and facilities designed for a smaller number of prisoners are required to meet the needs of many more.

The Queensland Ombudsman’s 2016 report on overcrowding at Brisbane Women’s Correctional Centre provides an important case study of how overcrowding can reduce access to services by prisoners including:

- Offending behaviour and substance abuse programs

- Education and training

- Health services

- Psychology services

- Recreational activities.

During the MCC visit, prisoners and staff identified the following impacts on prison infrastructure arising from overcrowding:

- Pressure on the kitchen and facilities for food storage

- Insufficient interview rooms

- Not enough seats for prisoners to sit on when all prisoners are out of their cells

- Insufficient rooms for psychological assessments, therapy sessions and programs

- Plumbing no longer adequate.

Overcrowding at centres also means there are not sufficient numbers of cells in detention units to accommodate all prisoners on safety orders, with some needing to remain accommodated in secure units while on the restrictive conditions of a safety order.

Impact of overcrowding on QCS’ humane containment objective

The impacts of overcrowding challenge QCS’ capacity to achieve its purpose of humane containment of offenders, as set out in s 3 of the CS Act:

(1) The purpose of corrective services is community safety and crime prevention through the humane containment, supervision and rehabilitation of offenders.

The humane containment purpose of the CS Act aligns with s 30 of the HR Act, which provides that: ‘All persons deprived of liberty must be treated with humanity and with respect for the inherent dignity of the human person.’

When considering what constitutes humane containment, it is important to have regard to the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules). The Explanatory Notes to the recently enacted Inspector of Detention Services Act 2022 identified that the Nelson Mandela Rules are generally accepted as good principles and best practice for the management of detained people.

Rule 12 of the Nelson Mandela Rules provides that:

Where sleeping accommodation is in individual cells or rooms, each prisoner shall occupy by night a cell or room by himself or herself. If for special reasons, such as temporary overcrowding, it becomes necessary for the central prison administration to make an exception to this rule, it is not desirable to have two prisoners in a cell or room.

Consistent with Rule 12, s 18 of the CS Act provides that: ‘Whenever practicable, each prisoner in a corrective services facility must be provided with his or her own room.’ While s 5A of the CS Act allows for exemptions from the HR Act to apply to the application of s18 in certain circumstances, it stands as an expression of Parliament’s intent for how prisoners ought to be accommodated.

Clearly, the accommodation of prisoners is a matter relevant to QCS’ statutory objective of humane containment. An area of administrative action that is important to QCS’ pursuit of this objective is how it advises government about its correctional facility capital program.

The task of closing the current gap of around 2,862 between the number of prisoners and the cells available to accommodate them is a significant one, particularly given the long lead time of capital projects to build new cells. Added to this is the need to continue to accommodate a growing number of prisoners, and the desirability of returning to a 90–95% facility utilisation rate. Also, QCS’ own forecasts are that prisoner numbers are likely to continue to grow in Queensland in the years ahead.

As noted above, QCS’ new prison, Lockyer Valley Correctional Centre, due to open in early 2024, will accommodate approximately 1,536 prisoners across 842 cells. This centre will undoubtedly relieve some of the strain on the state’s prison system when it is officially commissioned. The ongoing challenge for QCS is to continue to provide options to the government for a building program that will create the extra capacity needed to reduce the impacts of overcrowding.

In recent years, QCS has relied to a significant extent on its built bed program to address overcrowding. The utilisation of bunk beds is no doubt a faster and cheaper option than building more prison cells. However, the widespread and ongoing installation of bunk beds has also normalised a situation where our prisons are being expected to contain significantly more prisoners than the number for which they were originally designed. Relying on bunk beds as the long-term solution to overcrowding in Queensland prisons involves accepting increased strain on prison infrastructure, continuing impacts on prisoners’ mental health, dignity and privacy, and risks to the safety of custodial officers – and in so doing presents a fundamental challenge to QCS achieving its statutory objective of humane containment.

While bunk beds will undoubtedly remain an ongoing part of our prison system, it remains important for QCS to continue to advise the government of the importance of continued investment to expand the number of cells available for prisoners, so as to reduce the harmful impacts of overcrowding over time.

Based on the analysis of current levels of overcrowding in Table 1, priorities for QCS’ advice on options should include addressing chronic overcrowding at Arthur Gorrie Correctional Centre and increasing built cell capacity for female prisoners.

In responding to the proposed report (see Appendix D), QCS advised its current capital program includes the following key initiatives that aim to address capacity issues:

- $861 million ($341 million in 2023-24) to built the new 1,536 bed health and rehabilitation designed Lockyer Valley Correctional Centre (LVCC)

- $9 million ($1 million to complete round 3 in 2023-24 plus $8 million in released central funds for round 4) to install additional bunk beds in high security correctional centres across Queensland to manage the increasing prison population

- $3 million ($1 million in 2023-24) to complete the refurbishment of the Princess Alexandra Hospital Secure Unit

- $20 million in 2023-24 for pre-commencement activities including design works, site investigations and other preliminary works for the future expansion of the Townsville Correctional Precinct

- $10 million in 2023-34 for pre-commencement activities including design works, site investigations and other preliminary works for the future establishment of a new Wacol Precinct Enhanced Primary Health Care facility located at the Brisbane Correctional Centre.